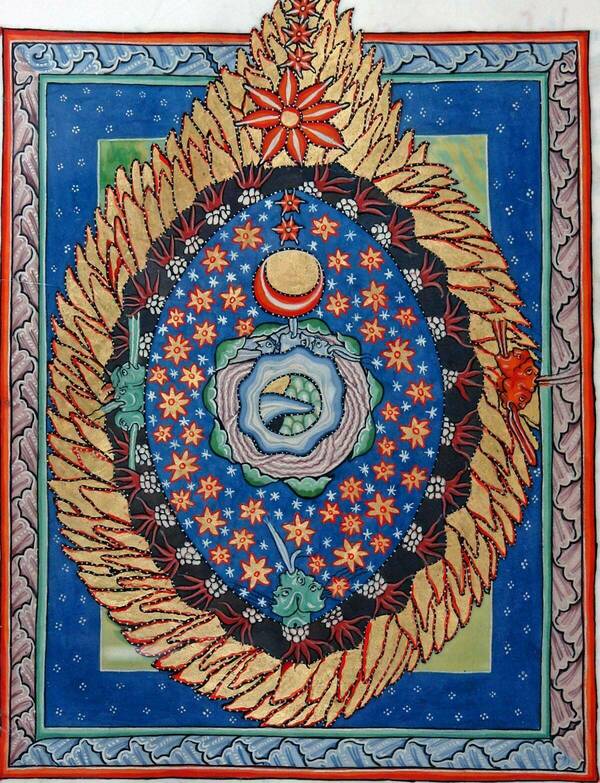

I’ve been meditating often of late about a question which is at the center of Christian Mystic thought: the metaphysics of God. In particular I find myself drawn to examining how God relates to the universe (his so-called “economy”). This inevitably draws me into questions about the nature of being, creation, becoming, time, and Eternity.

Traditionally, there are three general ways of thinking about this:

In classical theism, so mentioned first because it is best known to most people, there is a substance dualism between creation and Creator. When God created He did so such that a new thing was brought forth which had real existence outside of Himself. This created substance shared in only some of the features of the Deity who created it. Where the Divine substance is necessary, eternal, and infinite, the created substance is limited, contingent, and dependent.

Pantheism, on the other hand, collapses all distinctions. In this view, creation and God are simply the same thing. The world is God, and God is the world. There is no Creator–creature distinction, because all is divine substance. The problem, of course, is that evil, death, and imperfection then become aspects of God Himself. For this reason, pantheism has never found a comfortable home in Christian thought. It dissolves the mystery of transcendence into a flat identity between God and the world.

Panentheism (literally “all-in-God”) tries to hold both transcendence and immanence together. In this model, the world is within God, but God is more than the world. All creation participates in God, and yet God’s being exceeds it. This can sound attractive, and indeed many modern theologians speak this way. Gregory Palamas, the great Byzantine mystic, is often read as panentheistic when he says: “All created things participate in God and have their being in Him, not in His essence, but in His energies” (Triads I.3.23)). Creation thus exists truly in God, but without touching His innermost essence. Theosis — the transformation of the human into a “partaker of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4) — becomes possible precisely because our life is already a participation in God’s divine life.

I find the most compelling position which maintains all revealed Christian truth to be something I like to call “Divine Idealism.” Like in pantheism and panentheism, there is essentially only one substance: the Divine substance. There is, in fact, only one Being: God. But inside the mind of God there is a simulation playing out, and this is our world. In Divine Idealism, we are but a dream — but not an accidental dream. We are the dream God wills to have, first, and eternally.

In this sense I echo Augustine, who wrote: “The ideas are certain original and principal forms of things, stable and immutable, which are contained in the divine intelligence. They themselves are not created, but they are the forms according to which whatever is created is formed” (De Diversis Quaestionibus 83.46). In other words, everything that exists has its archetype as a thought in the divine mind. And yet, as Augustine insists in De Trinitate (XIV.11.15), God is not enriched by these thoughts, for He knows creatures “by Himself, nor is anything added to Him by such knowledge.” Creation is in God, and sustained by God, without changing or enlarging Him in the least.

Thus in Divine Idealism there is only one substance, the Divine substance. But created beings are held in being by the act of will of God, and thus participate in a non-essential way in continual existence. We are not consubstantial with God, for our being is not His essence. Yet we are real, as a dream is real to the dreamer. This, to me, harmonizes the insights of Augustine’s rationes aeternae (eternal archetypes in the divine mind) with Palamas’s vision of participation in the divine energies.